The First Model of the Violano Virtuoso

By Johhny Duckworth

With the Mills Violano-Virtuoso having such a fascination with collectors today, one can only imagine the impact it must have had in the early 20th century.

The machine was labled by the Mills Novelty Company as the worlds greatest musical attraction, as well as honored and designated as one of the greatest scientific

inventions of it's age by the United States Patent Office. Today, when you hear an expertly restored or correctly tuned Violano play, the piano the piano and

violin produce and unbelievable sound together.

With the Mills Violano-Virtuoso having such a fascination with collectors today, one can only imagine the impact it must have had in the early 20th century.

The machine was labled by the Mills Novelty Company as the worlds greatest musical attraction, as well as honored and designated as one of the greatest scientific

inventions of it's age by the United States Patent Office. Today, when you hear an expertly restored or correctly tuned Violano play, the piano the piano and

violin produce and unbelievable sound together.

The Violano-Virtuoso traces it's ancestory to the Automatic Virtuosa invented by Henry K. sandell, using a violin. These were invented as an amusment device for use in penny arcades,railroad stations, and other locations, circa 1906. Mills decided it was capable of more serious use, and performances were arranged with an artist playing on a nearby piano to accompany the violin. In 1908, an Automatic Virtuoso and pianist gave concerts in England After this success, Mills took the next step foward and incorporated a 44-note piano into the cabinet with the viollin. Sandell would also later devise a symmetrical piano plate around 1910, for wich he recieved a patent two years later. This piano placed the bass strings in the middle of the cabinet, resulting in a balanced tension of the piano plate, wich was intended to keep the instrument in tune longer. Some of the Automatic Virtuoso that had already been produced and shipped from the factory would later be traded back in or returned to have a piano added. The addition of the piano can be seen on the illustrated model, as well as some of the earlier bow fronts. You will notice the added piano with some of the early bow fronts by looking atthe curved cabinet design wich had to transition into a square back to hold the new piano. None of the early violin-only cabinets have ever been found without the piano added.

The model shown in this article is one of the firt Auotomatic Virtuoso case design used by the Mills Novelty Company, and it's the only surviving example known to date. This early case style didn't last long as it was replaced before they ever got it off the ground. It's believed that Mills started the Violano-Virtuoso production with serial number 101. the piano in this machine bears serial number 204. It's marked 9-27-1913, this date being located behind the hammers,wich indicates when the piano was installed. The lowest serial number for a Vioalno is on a home model, numbered 116. Some of the low serials wich are found on bow fronts are 139,146,156,163, 168,169,188, and 191 and the highest piano numbers reached just over 4900. Keep in mind the piano serial numbers are in order of when they were installed at the factory so you can't determine the original build date with the handful of the violin-only models. The early violin machines were being sent back to the factory to be fitted with a piano, while at the same time later machines had already been produced with the piano and violin combination. Those early violin machines will have a higher serial number on the piano, even though they were built at an earlier date.

This early case design has a large beveled window in front of showcasing the violin, with stained glass panels above the windows and doors. There are windows on each side of the cabinet,just like you will observe on a bow front modeland one early home model. This cabinet does have a few advancements. For example, the coin entry, wich was originally located on the right side, has now been placed in the front just like you will find on the later models. You can find several catalog photos of this model pictured in the Encyclopedia of Automatic Musical Instruments, by Q. David Bowers, on pages 508-512, while also being placed on the cover.

This particular machine has a piano plate marked "patent allowed Violano-Virtuoso U.S.A." Only a few of these early plates are known today. The violin bears serial number

247 and was produced by P.C. Poulsen, who worked for Mills from 1908 to 1919. The first mechanism to be used on a violin was the overhead prototype version with the strings

being fretted from the top. It also had an attachment for pizzicato wich is a term for "plucking strings." Today, only one Violano remains with this prototype overhead unit;

built for Herbert Mills and placed in his home. Acocording to Bert Mills, fewer than 20 of the overhead prototype mechanism were ever produced. With the numerous problems

they had, they were quickly updated with the early violin expression mechanism, between 1909-1910, wich today is known as the "early style." This early cabinet originally

held the prototype version only to be upgraded later at the factory during the piano installation. This early style expression was used into the late teens, and has been

observed as high as serial 20001.

This particular machine has a piano plate marked "patent allowed Violano-Virtuoso U.S.A." Only a few of these early plates are known today. The violin bears serial number

247 and was produced by P.C. Poulsen, who worked for Mills from 1908 to 1919. The first mechanism to be used on a violin was the overhead prototype version with the strings

being fretted from the top. It also had an attachment for pizzicato wich is a term for "plucking strings." Today, only one Violano remains with this prototype overhead unit;

built for Herbert Mills and placed in his home. Acocording to Bert Mills, fewer than 20 of the overhead prototype mechanism were ever produced. With the numerous problems

they had, they were quickly updated with the early violin expression mechanism, between 1909-1910, wich today is known as the "early style." This early cabinet originally

held the prototype version only to be upgraded later at the factory during the piano installation. This early style expression was used into the late teens, and has been

observed as high as serial 20001.

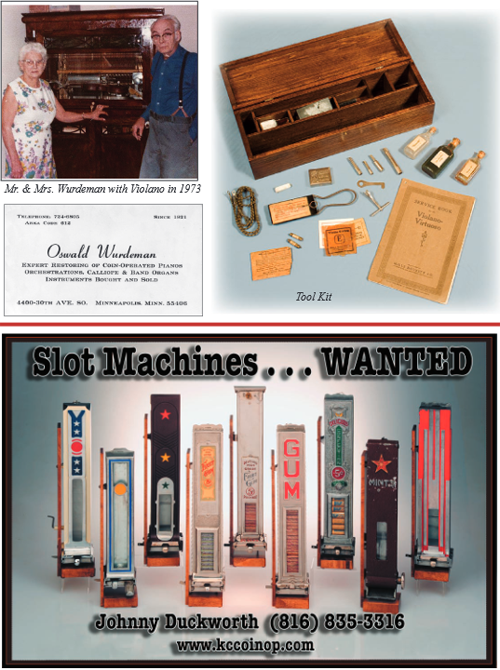

This early Violano was purchased by Mr. Oswald "Ozzie" Wurdeman, in October of 1969. Ozzie was the son of Edward "Ed" Wurdeman who had acquired a distributorship from the Mills Novelty Company in Minnesota, South Dakota, and North Dakota. Ed loaded up his family that year and moved from Nebraska to Minneapolis to start The Electric Violin Company. Ozzie was 21 when they moved to Minesota. He spent some time in Chicago at the Mills factory where he later became a trained serviceman on the Violano. The machines were very expensive back then, costin Ed $1,200 for a (single) Baby Grand, $1,600 for a Concert Grand, and $2,000 for a double Violano. Later in the 1920's, they started marketing the Western Electric piano and phonograpgh while continuing the Violano. Ed had taken out loans from the bank to pay for many of the over 350 machines he owned. When the depression hit in 1929, Ed lost his buisness, and the bank went under as well. As a result most of the machines were left standing, and Ozzie rounded up as many as he could before they vanished. He then took the piano plates out of the Violanos and sold them for scrap to buy groceries. The back doors with soundboards were also taken off, placed flat on their backs, and used to build his shop floor. The remaining wooden case parts were then broken up and burned in his wood stove during the cold winter months.

Ozzie could work on band organs, pianos, Violanos or any other musical machine. In the early 1930s, he started his own business selling and repairing band organs and calliopes. He found plenty of work at the area amusement parks and skate parks with their pianos and organs. He also worked on jukeboxes and pinball machines to keep up the business The Wurdeman family spent 19 summers in Virginia city, Montana, in the 50's and 60's working for Charlie Bovey, a wealthy entreprenuer who played a key part in preserving and displaying the historic buildings of that old mining town. While working in Montana, Ozzie stumbled across this rare Violano in a museum in billings. The museum was located in the Wonderland Park owned by Don and Stella Foote, who also owned another museum in Cody, Wyoming. The Footes exhibited some rare musical instruments , including a Seeburg Style H Solo Orchestrion at the Montana display and at the New York World's Fair in 1964, wich is now in the Bowers collection.

When Don passed away in 1968, Stella lost intrest in the museum and decided to sell off the collection wich included approximatley 58 instruments. She sent a list to Ozzie, who had worked on many of them, to help get her the correct and current pricing. The prices on Ozzie's list are very intresting today. For example, the Seeburg H was priced at $2,750-$3,250, a Violano double double at $1,000-$1,500, and a National Calliope for $1,500-$2,500. The list included this early Violano for only $400-$750, wich needed some work at that time, such as replacing the missing bass strings and piano magnets. Stella must have been a tough negotiator as Ozzie ended up buying the machine for $800, wich was little more than he had down on the list. The museum previously had Oziie convert the machine to play the more popular, later rolls. Surprisingly, after all those year I was able to acquire those early parts from his son Tom, who still had them in a box. Tom also had the original contract from 1921 between his grandfather and the Mills Novelty Company, the list of machines in wich Stella had provided his father, and the bill of sale on this early Violano. Tom acquired the machine when his father passed away from cancer in 1973. His family has been in the coin-operated business for three generations. Tom, just like his father, is known for his restoration work on these fine musical machines. Tom worked alongside his father when he was a boy to learn the trade and is currently in his 80's and one of the living links into this musical past. He sold this early style Violano in 2000, and it went into the Tomara collection.

I acquired the instrument in 2010, and sent it to the Haughawout Music Company in Ohio for a complete restoration. Terry has been restoring machines for 36 years and specializes in Violanos. He has worked on more than 600 such instruments, of which at least 150 have been completely restored back to their factory specifi cations. That’s an amazing number considering fewer than 25 percent of the original machines produced are known today. The rough estimates on the different models known are this early cabinet style, 11 home models, just over 20 bow fronts, over 50 doubles, and around 900 singles. That’s a very high survival rate for a coin-operated machine. It is believed that many of them were saved due to the violin located inside the cabinet, since they have always been a treasured instrument. Whatever the case may be, there are plenty of Violanos known today for everyone to listen to and enjoy in their collections.

I would like to thank my mentors who have helped me with valuable information on this article and have been a big influence to myself; David Bowers, Terry Haughawout, Art Reblitz

and Tom Wurdeman. In addition, I would like to mention Don Barr who was an early pioneer in Violano maintenance and history. Some of the information above comes from his

interviews with Bert Mills and subsequent articles he wrote for MBSI. I would also like to give credit to the Music Box Society International (MBSI) who previously printed this

article in their magazine. I hope to have a video of this machine posted on my website soon, at www.kccoinop.com

I would like to thank my mentors who have helped me with valuable information on this article and have been a big influence to myself; David Bowers, Terry Haughawout, Art Reblitz

and Tom Wurdeman. In addition, I would like to mention Don Barr who was an early pioneer in Violano maintenance and history. Some of the information above comes from his

interviews with Bert Mills and subsequent articles he wrote for MBSI. I would also like to give credit to the Music Box Society International (MBSI) who previously printed this

article in their magazine. I hope to have a video of this machine posted on my website soon, at www.kccoinop.com